MacGregor (Excerpts from Chapter 15)

The book reveals the discovery that the Murrays changed their name because of a famous historical prohibition in Scotland. The Murray ancestry was recently verified as really descended from a key lineage of ‘the MacGregors’ (traditionally a most resilient and pivotal Scottish Highland clan).

Excerpt #1: Introduction

Glen Orchy’s proud mountains, Kilchurn and her towers,

Glenstrae and Glenlyon no longer are ours;

…We’re landless, landless, landless, Gregorach!

But doom’d and devoted by vassal and lord.

MacGregor has still both his heart and his sword!

Then courage, courage, courage, Gregorach!

While there’s leaves in the forest, and foam on the river,

MacGregor, despite them, shall flourish for ever!

– An excerpt from the famous 1816 poem ‘MacGregor’s Gathering’ by Sir Walter Scott (born the same week in August 1771 as KM Sr)

MacDonald is the heather, MacGregor is the rock – traditional Highland saying.

Excerpt #2 The historical prohibition against Clan Gregor in the Scottish highlands

Following an earlier order made against Clan Gregor by King James VI in 1589, related Proscriptive Acts were first enacted in 1603 following the ‘pretext’ of the Battle of Glen Fruin. This preceded the devious execution in 1604 of the then Clan chief Alisdair MacGregor and eleven senior clansmen in Edinburgh by the King after the Campbells had enticed them there for a meeting with false assurances of protection. Also, according to the MacGregors, ‘Glen Fruin’ was the February 1603 battle where, despite being heavily outnumbered, they foiled an ‘ambush’ by the Colquhoun clan acting on behalf of the Campbells. With these Acts also extinguishing all previous land claims by the MacGregors against the Campbells, they represented a culmination of a process by which the Campbells (and Stuarts) had progressively ‘dispossessed’ the MacGregors of their traditional lands over centuries following Robert the Bruce’s decision to reward the Campbells for their participation in the Bannockburn victory of the English (in which the MacGregors had also fought for Bruce and Scotland) with the Barony of Loch Awe – which included significant Macgregor lands. Following the Proscription, any MacGregors who failed to give up their Clan Gregor name and allegiance were typically hunted down and the men then executed – with the women also regularly branded and exiled or enslaved (or worse). The term ‘hidden MacGregors’ refers to Clan Gregor descendants who had retained their post-1603 aliases or had just forgotten their heritage after the Proscription was finally ended for good by royal decree in 1774.

Excerpt #3 the Dean of Lismore’s Book by Sir James MacGregor (verified Kennedy Murray ancestor)

From a Clan Gregor perspective, the greater significance of the Dean of Lismore’s Book lies in how, in the later sections of this, it includes two related items of ‘MacGregor genealogy’ from the ‘present day’ of c1512 back to (and perhaps beyond) ‘Kenneth MacAlpin’. The first item from page 136 of the 1887 edition addresses the perspective of a MacGregor cousin to James and Duncan who died in 1526): “remember well thy back-bone line, Down from Alpin heir of Dougal, Twenty and one besides yourself”. This item goes on to mention that ‘of thy race which wastes not froth, six generations wore the king…’ (possibly with reference to the royal legacy of kings coming after Kenneth MacAlpin). With the additional context outlined below, there indeed does seem a credible basis for the view that the Clan Gregor may have been directly linked back to Kenneth MacAlpin first King of Scotland in 843 CE (or at least from the related ‘house of Alpin’ royal dynasty’ that survived until 1034 and included a King Girig or Gregor). And so, a possible further claim that the first King of Scotland Kenneth MacAlpin was the 30 X (or so) great-grandfather of Kennedy Murray Sr (and of his Australian descendants as well as others in Clan Gregor) likewise has some credible basis.

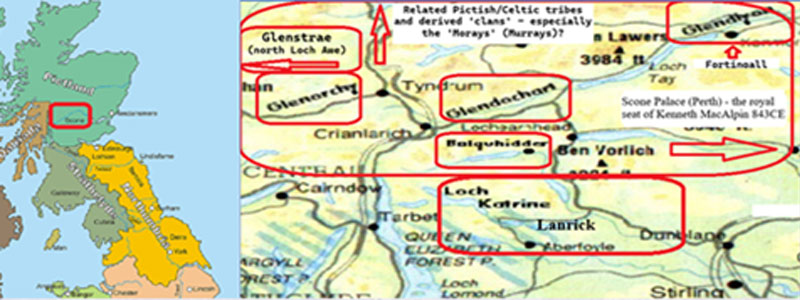

‘Macgregor country’ as also a cultural as well as geographical heartland (still) of both ‘traditional Pictland’ (Albann, etc) and ‘modern Scotland’?

The basic ‘authenticity’ of the Dean of Lismore’s Book as a retrospective written translation of a largely oral tradition has generally been confirmed by Scottish cultural historians and not just representatives of Clan Gregor. But what about its role in helping to explain how and why the Clan Gregor motto is ‘royal is our blood’ (‘S Rioghal Mo Dhream)? Even within Clan Gregor there are two (i.e. ‘traditional’ and ‘modern’) perspectives on the genealogy of the MacGregor ‘ancestral family tree’. This is as well as the retrospective ‘truism’ of how, as Peter Lawrie has written in his article ‘the early history of Clan Gregor’, “highland clanship came out of a fusion of Celtic tribalism and Norman feudalism during the 12 and 13th Centuries” [At this time fixed ‘surnames’ (including the formalising of patronymic names – usually by affixes like the use of ‘Mac’ or ‘son of’ in Scotland) were instituted around Europe as part of edicts linked to motives of administration and taxation].

But the two perspectives can and perhaps should be seen or taken as ‘complementary’. In this view there may be some particular discrepancies in the names mentioned in the Dean of Lismore’s Book genealogy by an associate of the Dean. But the link back to the royal house of Alpin over ’22 generations’ might well be generally true whatever some possible ‘quibbling’ about the details – or whether one might focus on Kenneth MacAlpin’s generally agreed-upon ‘royal lineage’ rather through the lens of his father’s Dal Riada (Scottish Gaelic) family or his mother’s Pictland (Pictish Celtic) family.

The term ‘Celtic tribalism’ incorporates some quite different as well as similar Pictish and Scottish Gaelic (i.e. earlier Pictland and Dalriada) contexts and meanings. This distinction also applies when such a term is used to refer to earlier ‘Clan members’ before Clan Gregor adopted both a ‘Norman feudal’ system and a ‘Gaelic Scottish’ Chief for the first time in the mid-14th Century. This is perhaps as much because (rather than despite how) the various sections of ‘MacGregor Country’ also reflected the growing merger and related ‘inter-marrying’ of Picts and Gaels in similar fashion to the example of Kenneth MacAlpin’s parents (i.e. the reported union between MacAlpin’s Dalriada Gaelic father and Pictish mother). As reinforced by the evidence of the Dean of Lismore’s Book (i.e. that the traditions of Scottish Gaelic were distinct from, not merely derivative of, those of Irish Gaelic), some have argued (with a credible basis for doing so) that the Dalriada ‘Cruithne’ of Ulster as well as the Western Scottish highlands were perhaps together originally an off-shoot of the earlier Picts and not the original Irish ‘Celts’ of the greater Ireland. If so, then this was a Pictish off-shoot which soon adopted the Gaelic language and also writing, and then brought it ‘back’ to Pictland where it became dominant after later also being adopted by the Picts in the emerging Scotland.

The modern or ‘Norman feudal’ tendency to focus more or mostly on the lineage or succession of Clan leadership (in some aspects similar to the Gaelic ‘Tanist principle’) may well apply reasonably well to other and especially ‘lowland’ Scottish clans. But this perhaps needs to be complemented also by a more traditional focus when it comes to recognizing how (as reasonably self-evident from the two linked maps below) the Clan Gregor emerged at least as much (if not more) out of Pictish as ‘Scottish Gaelic’ Celtic tribalism. This is especially so in light of the compelling admission by Forbes MacGregor in his 1977 book Clan Gregor that “the astounding thing is that the main body of MacGregors is of Pict ancestry but not the old line of Chiefs”. The leadership lines of Clan Gregor from the mid-14th Century onwards (as distinct from the tribal leadership of earlier centuries) generally involved male heads of families within the Clan located or particularly associated more with the Clan lands in Argyllshire (part of the former Dalriada) to the West (i.e. the ‘Lock Awe’ areas of Glen Strae and Glen Orchy). In contrast many other ‘Clan members’ were perhaps as much (if not more) derived from Pictish tribal origins. This was likely to be especially so in the Eastern sections of ‘MacGregor Country’ towards Perthshire like Glen Dochart and Glen Lyon and Balquidder (the resting place of course of the most famous MacGregor ‘outlaw’ – Rob Roy).

It is generally recognized that ‘the first Chief of Clan Gregor’ c’1350’ (Gregor of the Golden Bridles) was located in the ‘Glenorchy’ branch of the family. But there are some interesting, related bits of relevant information about this. One is that this was evidently after (not before) the traditional tribal lands of this family had been directly threatened (and some effectively lost) by the earlier awarding of the Barony of Loch Awe to the Campbells by Robert the Bruce. Usually under the Norman Feudal scheme (of King David and others) Clan Chiefs tended to become the nominal landowners of traditional tribal lands – as well as becoming part of the new ‘nobility’ of Scotland part of the same network as the ‘Norman Lords’ [‘Frenchified Vikings’ who were effectively invited ‘back’ to Scotland around the same time as the Norman military conquest of England in 1066]. But in this case the prior loss of Clan Gregor land to the Campbells was later extended East to even include Glen Lyon before the time of Sir James MacGregor.

The linking of emerging Clan Chieftains with the apparent adaptation of the more hierarchical Gaelic ‘Tanist’ system of traditional tribalism and leadership succession compared with the more ‘egalitarian tribalism’ of the Picts – and their rather ‘matrilineal’ and related or resulting ‘extended family’ frameworks of leadership succession (as well as their more collective approach to tribal land ownership). It seems some believe that this ‘convergent perspective’ helped inform a related decision about this time to nominate Clan Gregor instead of the MacGregor Clan (i.e. give up the ‘Mac’ in the name of the clan to include other extended members of the tribe or clan). It might also help explain the apparent diversity of ‘MacGregor lines’ in the Clan Gregor DNA Project.

In any case, a more traditional perspective was typified by the 19th Century accounts by William Skene and Sir Walter Scott in particular. They both projected a prominent role of Clan Gregor within the traditional history of the Scottish Highlands linked to Celtic tribes – generally recognising the ‘royal is our blood’ claims of the MacGregors back to earlier Celtic royalty (i.e. from Pictish and/or Scottish Gaelic ‘royalty). In his 1880 volume ‘Celtic Scotland: A history of ancient Alban’ Skene supported a general contention that an original centre of ‘MacGregor country’ was Glen Dochart. This was not just because this was central between Eastern and Western families or branches. It was rather because the links back to royalty were believed to have connected with emergent local clans linked to the known hereditary Pictish Abbots of Glen Dochart. Sir Walter Scott was even more influential in remembering Clan Gregor role in Scottish highland traditions.

In the article cited above, Peter Lawrie supports a contention that directly associated with ‘the family of the Abbot of Glen Dochart’ was a ‘Clann Alpein’ as well as ‘Clann an Aba’. In other words, this is a notion that in the 14th Century Clan Gregor emerged from the earlier Clan Alpin centred around Glen Dochart like closely related clans like the MacNabs (son of ‘the Abbot’), MacKinnons (son of Finghin), MacAlpins and Grants, etc. Finghin was the Pictish Abbot of Glen Dochart (an abbey founded centuries earlier by the Celtic Christian missionary Fillan). In 966 CE he had apparently sought and obtained Papal (Rome) authority for Pictish monks to marry and produce their own local tribes or clans. According to tradition, this is how the hereditary abbots of Glen Dochart (believed by some to have been also descended from or otherwise related to Kenneth MacAlpin or others from his ‘royal house of Alpin’) also gave rise to related tribal families in the area from which Clan Gregor emerged as perhaps the ‘central’ or most pivotal clan. This connection would also help explain the ‘Soi Alpin’ tradition of the seven highland clans claiming descent from ‘Clan Alpin’: Grant, MacAulay, Macfie, Mackinnon, Macnab, and Macquarie as well as ‘Gregor’.

Furthermore, we should point out that the c800 map below of Pictland fails to mention how both the Gaels and Picts were both under severe pressure at this time from the Vikings to the North and East as well as West – as well as by the Strathclyde ‘Britons’ and the Northumbria ‘Anglo-Saxon’ forces. It is clear that this was the main reason why the Gaels and Picts generally agreed over time to work together against a common ‘foreign enemy’. This was perhaps the pivotal basis on which they later merged (or rather why the Picts were ‘assimilated’ as Scottish Gaelic took over as the dominant language). This was also perhaps the related reason why even much earlier the Picts apparently agreed to allow a son of a Dalriada Gaelic King to also become a ‘Pictish King’. And that may be the related reason why a similar merger or agreement perhaps took place within the emerging ‘Clan Gregor’ between some families to the West that it seems were predominantly ‘Gaelic’ and others to the East that were likewise predominantly ‘Pictish’.

L. Map of Pictland c800 CE. R. ‘MacGregor country’: The cultural as well as geographical ‘heartland’ (still) of modern Scotland as well as ancient ‘Pictland’?

The future Scotland is believed to have become a Pictish Celtic homeland centuries before the Romans under Julius Ceaser invaded around 55 BCE. This was also well before the Romans were sufficiently repelled by the hardy, resilient and fearful ‘Caledoni’ or ‘Pictii’ warrior tribes (as Agricola and others called them until the Romans departed from Britain in 410 CE) that they had built first Hadrian’s Wall to the South and the later Antonine Wall between the Firths of Forth and Clyde to simultaneous keep out or in the tribes to the North of this. In other words, the Southern highland Picts especially had occupied the heartland of the future Scotland for at least 1000 years before the royal crowning of Kenneth MacAlpin in that general area in 843 CE. This was arguably so as part of one of the last great surviving ‘warrior societies’ of Europe. And now (with new linguistic and DNA evidence and a better understanding of this) we can recognise that Pictish Celtic influence was more than just another linguistic and cultural ‘layer’ on the genetic foundations of the mainly original peoples that still survives today in modern Scotland.

The traditional highland saying ‘MacDonald is the heather, MacGregor the rock’ (i.e. the earlier Celtic tribe and later clan in ‘MacGregor country’) epitomises a larger recognition that the Scottish highlander influence has generally been pivotal to all this. This is notwithstanding the apparent ‘Mi run mor nan Gall‘ tendencies of some ‘lowlanders’ in 17th and 18th Century Scotland to ‘look down on highlanders’. This is of course similar to how some city-born Australians have long ‘looked down’ on and likewise ‘under-estimated’ those from rural or provincial areas. No wonder then that even before ‘Culloden’ (as well as more so afterwards) ‘highlander’ soldiers and regiments were becoming recognised as a backbone of modern British armies – as Harry Murray was clearly aware.

In his well-known works of ‘historical fiction and romance’ such as his famous novel Waverly, Sir Walter Scott brought alive the ‘historical past’ of the Scottish Highlands, its culture, and its ‘fate’. And with the related ‘Waverly novels’ such as Rob Roy and extended poems such as The Lady of the Lake (as well as other memorable shorter poems like ‘MacGregor’s Gathering’), Sir Walter Scott (born the same week in 1771 as KM Sr) regularly revisited the MacGregor (and related ‘Clan Alpine’) legacy which so inspired him. A recent Hollywood movie with Liam Neeson in it has helped reinforce that Scott today is still linked with the ‘legend of Rob Roy MacGregor’. For some (especially for Scottish lowlanders and the English), this was a romantic legend of how the historical Rob Roy became an ‘outlaw’ associated with cattle ‘theft’. However, for others he was a ‘highlander cattleman’ who became ‘the Scottish Robin Hood’. This was whilst he claimed to be fighting for justice against the Duke of Montrose – who (he believed) robbed him and his family of their lands and future. Rob Roy’s story thus epitomises that of the wider Clan Gregor over a number of centuries (i.e. the MacGregors having to resort to their pastoralist skills to survive after the unfair loss of traditional lands).

Scott’s version also focused on the historical Rob Roy’s heroic involvement in the ‘second Jacobite rising’ against the English crown in 1715. This was some years after Rob Roy was forced to become a ‘hidden MacGregor’ (1683) because of the restoration of the temporarily lifted prohibition against Clan Gregor. In any case, the main resonance of ‘Rob Roy’ with a Scottish (and indeed, international) audience is similar to that of Ned Kelly in Australia. Despite the efforts of some to downplay this (or to call either a ‘common criminal’), both are associated with the battle against the perpetual injustices and betrayals of an entrenched unfair system. Since the late 19th Century, this is why Australians have typically used the expression “to be as game as Ned Kelly” to refer to someone being brave against overwhelming odds.